The Fear Itself

Most complaints about “uncontrolled immigration” focus on so-called “illegals” crossing “the southern border.” The fear is that Spanish-speaking or Latino people will soon be a majority in some states.

That concern led me to look more closely at the history of immigration to the Americas from Spain and Portugal—and how it has shaped demographics from the United States through South America. Many might be surprised by what I found.

Spanish-speaking immigrants aren’t one race. Latin America includes people of Indigenous, African, European, and mixed ancestry—usually Indigenous and European, sometimes African. Treating all Latino immigrants as a single brown group isn’t just prejudiced. It’s inaccurate.

Across Latin America, racial makeups vary widely: Uruguay and Argentina are majority European by ancestry. Peru and Bolivia have large Indigenous populations. Brazil is split among white, pardo (mixed), and Black groups.

Language doesn’t equal race. If the concern is who’s coming, the answer depends on which country you look at.

Start with facts, not stereotypes. Our policies—and our tone—should reflect that complexity.

Turning the Lens: What History Actually Shows

Spanish and Portuguese migration began centuries before the United States existed. Much of Latin America was settled by Europeans—first Spain and Portugal, later Italy and Germany—producing mixed and sometimes majority-European populations.

Unlike the English colonies that became the United States, Spanish and Portuguese colonies brought few European women and discouraged strict racial segregation. Intermarriage—sometimes voluntary, often coerced—was common, creating layered societies of mixed Indigenous, European, and African heritage.

A Spanish or Portuguese last name—or language—doesn’t determine someone’s race. Latin America is racially diverse because of colonization, the slave trade, and centuries of migration and mixture.

Some countries have large populations with mostly European ancestry; others are majority Indigenous or mixed; many have strong African-heritage communities.

Demographic snapshot (recent census and survey estimates)

Argentina | ~97 % European (Spanish, Italian) | European-majority southern cone example.

Brazil | 45 % mixed, 43 % white, 10 % Black | European-African-Indigenous blend at scale.

Colombia | ~58 % mixed, 20 % white, 10 % African descendant, 4 % Indigenous | Wide regional variation.

Peru | 60 % mixed, 26 % Indigenous, 6 % white | Strong Andean Indigenous presence.

Mexico | ~65 % mixed, 20 % Indigenous, 15 % white | Large, diverse population with a wide regional range.

The southern cone (Argentina, Uruguay, Chile) leans heavily European; the Andes remain deeply Indigenous; Brazil, Colombia, and the Caribbean are more racially blended with strong African roots; Central America skews mixed.

Many of the same countries that send the most immigrants to the United States—Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Peru—also show how deeply Europe, Africa, and Indigenous America are intertwined. The U.S. debate often treats them as one group, erasing that variety.

Spain and Portugal are as European as England or Germany. The people who colonized the Americas brought European languages, faiths, and systems that were every bit as Western.

When someone treats a Spanish-speaking immigrant as less European than an English-speaking one, it shows how racism and xenophobia blur together.

Treating Spanish as a racial marker misses the point—and the people. Our tone and our policy should match that complexity.

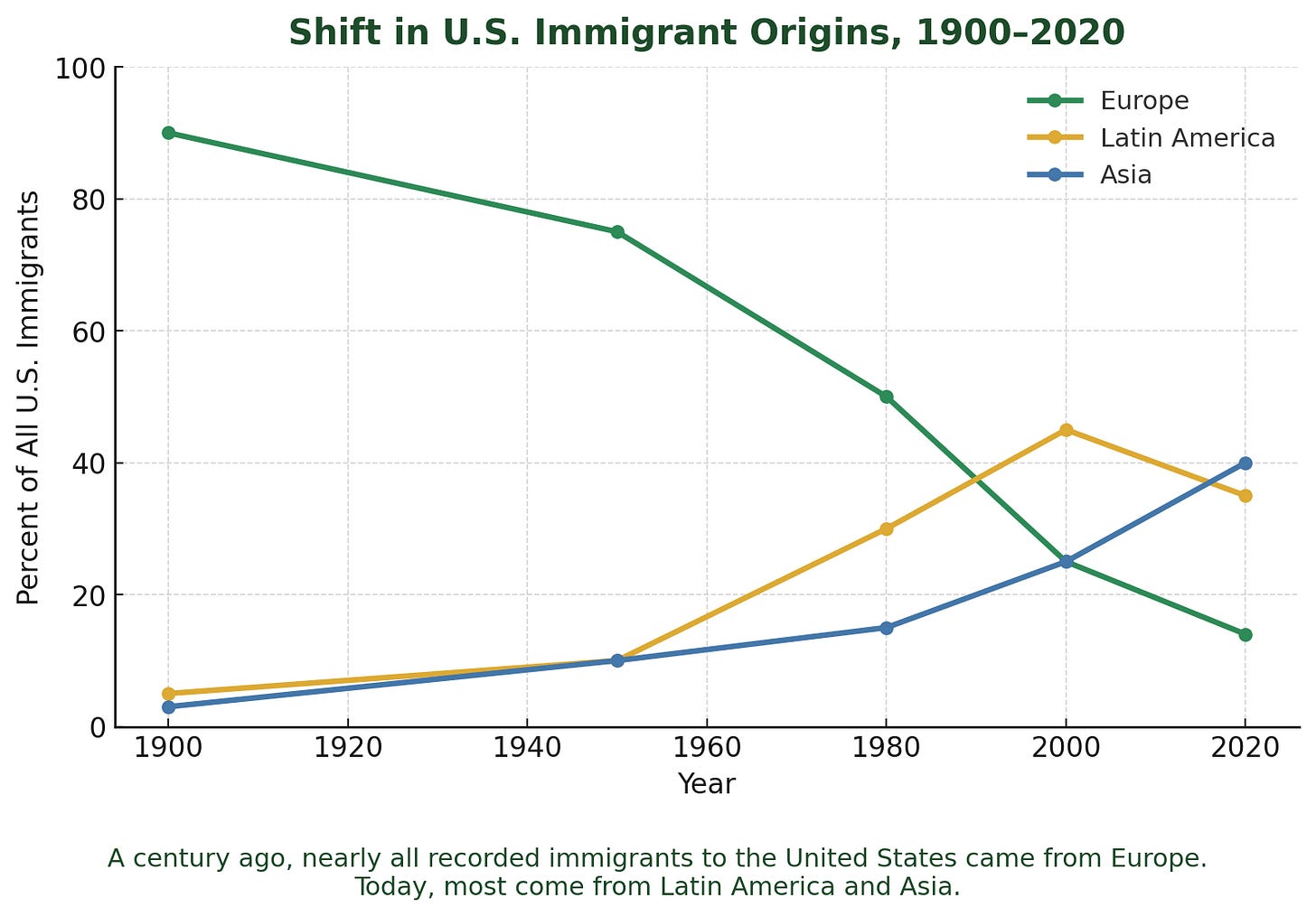

The Charted Story: Who’s Been Coming

The data show a clear shift: From 1900 to 2020, Europe’s share of U.S. immigration fell steadily while Latin America and Asia rose—an arc from European dominance to global diversity.

These numbers reflect immigrant flows, not ancestry. The people counted are those who crossed borders, not those whose roots long predate them.

After the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, quotas favoring Europe were replaced with a system emphasizing family reunification and job skills. That opened U.S. doors more widely to Latin America and Asia. The change wasn’t an invasion; it was policy.

These figures track arrivals, not family trees.

Even before the 19th-century waves from Ireland, Italy, and Germany, what became the United States was already shaped by migration—mostly from Britain, and by the forced migration of Africans. South of the border, Spain and Portugal had filled their colonies with settlers centuries earlier.

The Americas were shaped by many migrations—first by Indigenous peoples moving across the continents, later by Europeans and Africans who came by choice or by force. The land was never empty, only renamed.

The Americas were peopled by Europeans long before today’s debates about who belongs here began.

The Border That Moved

Before 1848, nearly half of today’s U.S. land—including all of California, Nevada, and Utah, most of Arizona and New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma—was Mexican territory, and before that, Spanish colonial. Mexico also gave up claims to Texas under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

In much of the Southwest, Mexican ancestry didn’t cross the border—the border crossed it. Those families weren’t immigrants in any meaningful sense, yet their descendants are often treated as such today.

Census and migration data focus on people who crossed international lines. They don’t capture this inherited presence, which means part of America’s so-called immigrant population has, in fact, always been here.

In the Southwest, Mexican heritage predates the United States itself. The border shifted, not the people.

Legal status is a different debate. This one is about origins and identity—about who we’re talking about before deciding what should happen next.

The Missing Chapter: Forced Migration

None of the charts or tables reflect the millions of Africans brought to the Americas by force. Their story is inseparable from the history of immigration yet rarely appears in its data.

Earlier centuries saw the forced migration of millions of enslaved Africans—a central chapter in the population story of the Americas that the chart doesn’t show. Noting that history doesn’t distract from this debate. It reminds us who built the Americas.

Putting the Pieces Together

Step back and the pattern becomes clear: The Americas have always been multilingual, multiracial, and deeply interconnected. The movement of people—voluntary or forced—has shaped every society on this side of the Atlantic.

Even when headlines say, “Latin American immigration,” they flatten real differences in why people move and from where:

Latin American migration to the U.S. today (approximate stock or trend)

Mexico | ~10.9 million | work, family, economic opportunity.

Venezuela | recent surge | economic and political crisis.

Brazil | growing numbers | economic and skilled migration.

Colombia | growing numbers | economic opportunity, post-conflict migration.

Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras (Northern Triangle) | over 3 million combined | violence, poverty, and climate-driven crop loss.

Cuba | ~1.3 million | Political repression, economic collapse.

Dominican Republic | ~1.28 million | family networks, economic opportunity.

Most leave for the same mix of reasons people always have: work, family, safety, and hope. No single country or ancestry defines Latin America; the range itself is the point.

Latin America’s diversity includes both European-descended elites and Indigenous and Afro-Latino communities, who often bear the brunt of inequality and violence.

The broad fear about “Spanish-speaking people taking over” ignores the real diversity within Latin America — from descendants of European settlers who often hold economic power, to Indigenous and Afro-Latino communities who have long faced poverty, discrimination, and violence.

Many newcomers trace their roots to Europe, while others are escaping conditions shaped by those old inequities and by more recent turmoil.

The fear of newcomers often ignores that most of our ancestors were newcomers—or never crossed a line at all. Long before borders, Indigenous nations lived and traded across these lands. The languages, religions, and customs we now call American began as imports, then intertwined here.

When people talk about foreigners, they’re often reacting to language and skin tone more than to actual difference. A Spanish-speaking family from Buenos Aires may share more European ancestry than a white family from Boston—but that nuance disappears in a debate fueled by fear.

If we can hold that complexity in view—Indigenous, European, African, Asian, and blended roots—we might see that immigration hasn’t replaced America; it’s always been America.

Closing Reflection

Facts can’t erase fear, but they can puncture myths. The numbers and history remind us that borders are recent, but belonging runs deep.

The continent that once filled America’s ships is no longer the source. But its languages, its people, and its shared history have been here all along.

Facts may not sway people who see only accent or skin tone. They still matter. Ignorance shouldn’t set the borders of truth.

To Learn More and Take Action

🟧 Latino & Hispanic Communities / Grupos de defensa de las comunidades latinas e hispanas

A ranked guide to organizations promoting justice, equity, and opportunity for Latino and Hispanic communities across the U.S.

🟥 Immigration Rights

A ranked guide to advocacy groups defending the dignity, safety, and civil rights of immigrants in the United States.

Share

If my commentary resonates with you, please share it with friends.

Subscribe

Get new posts from Plainly, Garbl delivered to your inbox.